Researching ways autistic people use different ‘styles’ to process information

By Anna-Francesca Boatswain-Jacques and Jacob A. (Jake) Burack

The motto of the McGill Youth Study Team (MYST) is “excellence in the study and education of all children.” The team is directed by Dr. Jake Burack from the department of Educational and Counselling Psychology at McGill University and includes graduate students from the School/Applied Child Psychology and Human Development programs, as well as undergraduates and other volunteers. The starting point of all our work is that of a shared humanity among all people, regardless of place of birth, ethnicity, race, culture, history, experiences, status and well-being.

From within that universal and humane framework, we embrace group and individual differences in attempt to create a society that is ideally inclusive, empowering and enabling for each person in their own way. Rather than concentrate primarily on deficits or challenges, our focus is on the strengths inherent in all people. In that framework, we work and collaborate with a range of communities, such as Indigenous youth, people experiencing homelessness, those living in poverty and intellectually disabled youth. Across all these groups, we challenge often prevailing deficit or pathologizing narratives and focus on alternative ways of being.

Our work with the autistic communities highlights the foundational values of our research approach. Over the past few years, we have shown through experimental research that autistic children and adolescents attend to information in different ways than do others – not because they are not as good at it or even because they are better (which they are in some cases), but because they use different styles, have different biases or are motivated by different factors. In fact, we argue that autistic people may be more “data driven” and even more efficient attenders in certain situations because their styles can lead to less distraction from the task at hand. We have termed this approach as “utilitarian,” to reflect its useful and practical nature.

Through this research, we have debunked certain myths about inherent deficits in autism. The first myth was that autistic people cannot process whole images or see beyond the simple sum of parts (such as missing the forest and seeing merely the trees). Along with others, our team has challenged this idea, showing that autistic people can process the full picture just as well as anyone else of the same developmental level when they are instructed to do so. The true difference, rather, lies in situtions where they have the choice to process either the big global picture or the smaller local details. Non-autistic people almost always begin processing the global picture by default while autistic people tend to prefer more fine-grained local approaches. So, the question is not about better or worse, but, instead, about different default styles.

A second myth was that autistic persons cannot integrate information from different senses, like sight and sound. We debunked this myth by showing that sounds and sight can be processed just as accurately and quickly by autistic people as non-autistic people. Although performance was similar between the groups, their brain activity was quite different. In fact, the brain activity of autistic people showed a much quicker response to incompatible sight-sound combination and showed greater activity in areas linked to perception. These findings show that sensory integration is processed by autistic people but in different ways than among non-autistic persons.

A third common myth is the belief that autistic people cannot follow the eye gaze of others, which is a critical social behaviour.

While researchers have shown important differences in the use of eye gaze between autistic and non-autistic people, the reality is more complex than simply stating what each group can and cannot do. Instead, we found that autistic people follow eye gaze when there is clear reason or incentive, and they benefit from doing so. This style of attending to eyes is different than that of non-autistic peoples who follow eye gaze more automatically.

In choosing to explore “how” – not simply “how well” – people process information, we seek to discover the mechanisms underlying different ways of thinking observed in autistic people, thereby allowing us to learn more about the development and workings of the mind more generally. In proposing utilitarian processing – a new way of thinking about the differences between autistic and non-autistic people – we argue that autistic people are less swayed by prior knowledge or assumptions that generally affect how others think. Rather, we suggest that autistic individuals actively choose relevant information based on their immediate context. Accordingly, they can more accurately process the available information, thereby leading to unique insights that others might miss. The goal of all this work is to facilitate a more inclusive and empowering worldview by better understanding how diverse styles of processing can lead to different ways of seeing and interacting with the world.

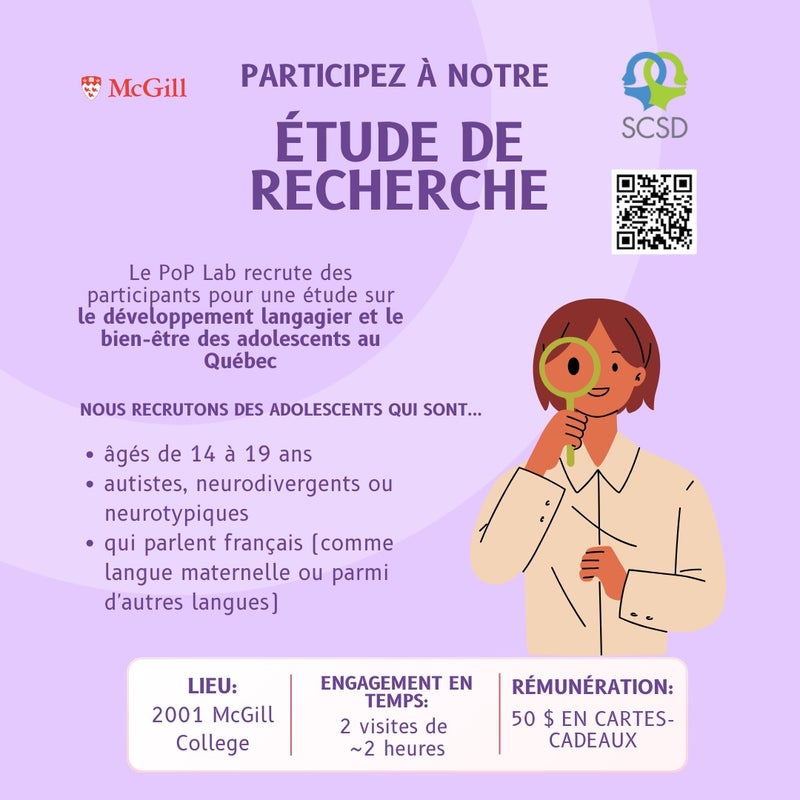

If your neurotypical or neurodiverse children would like to participate in this research, please contact us at mcgillmystlab@gmail.com for more information.

Anna-Francesca Boatswain-Jacques is a Ph.D. student in the School/Applied Child Psychology Program in the department of Educational and Counselling Psychology at McGill University.

Jacob A. Burack, Ph.D., is a professor in the department of Educational and Counselling Psychology at McGill University; director, McGill Youth Study Team (MYST); and scientific director, Summit Center for Education, Research, and Training.